"Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth? ... When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?" -Book of Job 38:4-7

The experimental epic film, The Tree of Life, by Terrence Malick (2011) begins with a mysterious floating light flickering in a vast darkness.

In the next scene, it’s the 1960’s and Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien are informed that their 19-year-old son, R.L., has been killed. The news sends the family reeling. They ask God why it had to happen. Why him? What does it mean?

The film then jumps to 2010 where R.L.’s older brother, Jack, wanders through a modern urban landscape, depressed, reflecting upon his life and work which lack fulfillment and beauty.

The film then takes another abrupt leap to a montage depicting the Big Bang, the birth of the universe, the formation of the Earth, and ultimately the dawn of life.

Later we witness the coming-of-age of the O’Brien brothers in the 1950’s, against a backdrop of epic natural beauty intermixed with family drama, spiritual musings, and dream sequences.

The film’s final act shows the adult Jack experiencing a vision resembling the Rapture, where he reunites with everyone he knew as a child, then finds his brother and brings him to his parents who kiss him, say goodbye, and willingly send him off into the bright and beautiful unknown.

After the vision, Jack exits the cold and colorless office building where he works, and smiles as he looks around at his surroundings, noticing again, for the first time since he was a child, how beautiful and glorious the world is.

The film’s last shot is the same as the first: a mysterious flickering light floating in darkness.

The Tree of Life is a strange but brilliant movie; the kind that only gets ‘1/10’ and ‘10/10’ ratings on IMDB. People think it’s genius; people think it’s pretentious trash. I think it’s a poem projected onto a screen which attempts to convey—aesthetically, rather than explicitly—the nature of existence itself and, simultaneously, what it’s like to exist.

Terrence Malick surely intended the film to come off as mysterious and defy analysis—just like God’s works mystified Job—but I am going to, of course, endeavor an analysis anyways.

The mysterious light depicted in the opening and closing shots is the Torch: the thing we inherit from our ancestors and pass down to our descendants; the energy of becoming that flows within all things; the thing that ties us to the past and links us to the future; the thing that connects each and every living thing to the same ancient origin and, therefore, each other.

The film seems to convey, repeatedly, that everything is connected.

And the film muses on that interconnectivity by jumping around a lot—from person to person, time period to time period, cosmic event to cosmic event—as if to say: the death of a boy and the birth of the universe are part of the same story; that the evolution of dinosaurs and a man’s mid-life crisis are actually linked. As if to say everything in existence is just one big pattern, one big entity—like many branches of one tree.

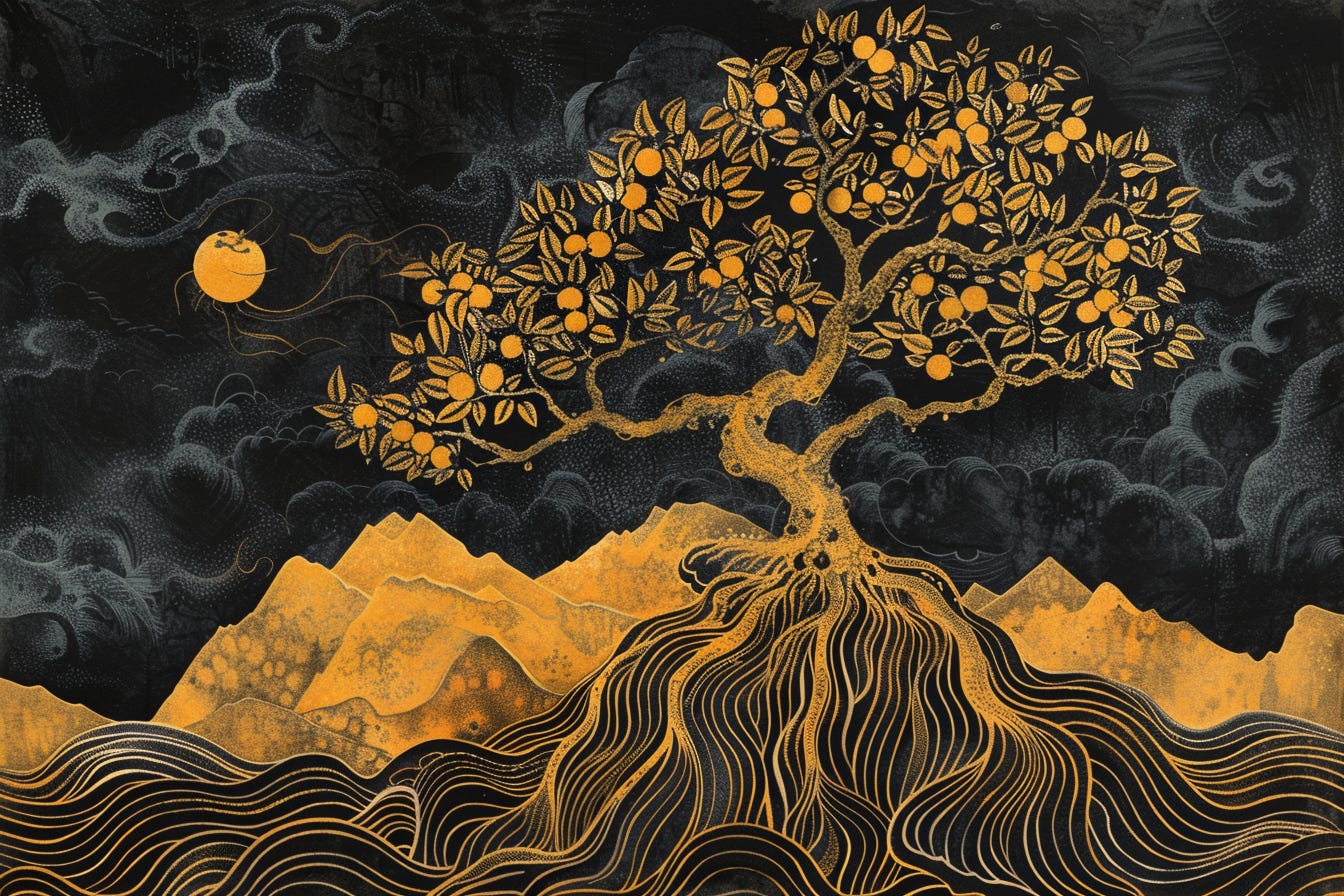

The Tree of Life spends a surprising amount of time depicting the birth and ensuing growth of the universe. As if to say that the cosmos—which at the time of the Big Bang was smaller than a grain of sand, but grew into a universe 15 billion light years wide—has the same divine force propelling it as a tiny seed that grows into an enormous redwood. That the little primordial pin drop that began all of existence, wriggled and danced into a complex constellation of galaxies and stars, like golden fruit dangling from the celestial branches of a great cosmic tree—the Tree of Life.

Some of those golden fruit ripened into planets, and then that divine fractal planted new seeds, which sank their roots into the primordial ooze and sprouted self-perpetuating molecules that branched and branched and branched into all the species of plant and animal life that roam the Earth today.

The film implies that the galactic tree, the phylogenetic tree, the family tree, and the literal tree are all expressions of the same cosmic nature, the same spiraling spark, the same stream of existence that wills itself further and further along a divine and mysterious path to produce the world we see around us.

And we are part of that path, part of that transcendent spirit unfolding in the cosmos. We are a tree.

But what is a tree?

There is a pervasive myth—or perhaps a confusion—that would have you believe that a tree is an individual. That a tree is just this discrete physical object, no different than a telephone pole or a street light—but that’s wrong. A tree is more than an individual physical object: it’s a living pattern. It’s one link in a chain of trees stretching back to the dawn of life. It’s a superficial manifestation of a living entity that is over 3 billion years old.

The tree came from a seed, which came from a tree, which came from a seed, which came from a tree—a pattern that goes all the the way back to the first self-replicating molecule. The tree will produce seeds, which will grow into trees, which will produce seeds, and the chain will continue, indefinitely.

So it’s more accurate to say that the ‘true’ entity is not the individual tree but its lineage, this stream of life that’s been traveling, growing, and unfolding for billions of years. And that this specific instance of the tree, this individual body, is just a part of a whole, something that’s been constructed around the lineage to ensure its survival.

To illustrate, there is a species of tree, tachigali versicolor—also known as the ‘suicide tree’—that reproduces only once in its lifetime and then dies. This tree lives in the rain forest and grows to around 100 feet tall. Its life cycle is like this: it grows from a seed for about five years and gets very tall, then it flowers once, then within a year it dies, and falls over.

Why? Doesn’t the individual tree want to keep living at all costs, for as long as possible? Doesn’t it want to protect its ‘self’?

Yes, but the individual body of this single tree is not the ‘self.’ The self is the lineage. When the parent tree dies it creates an opening in the canopy—a breach in the forest ceiling—that gives the seedlings an opportunity to receive valuable sunlight and take their parents’ place. The parent tree sacrifices its individual existence to propel a future generation, to pass the Torch onto the next manifestation of the lineage.

The body of the tree—this construction of wood and bark and branches and leaves—is a suit of armor protecting that true entity, the Torch. And you can see that in everything the tree does, everything the tree is. The leaves absorb light and the roots drink water, so the tree can grow strong and produce seeds and the seeds can sprout roots and leaves and the cycle can begin anew. Seed to tree to seed to tree to seed, as if there really is no beginning or end to the being in question, as if it’s all one entity, one chain of energy, spiraling through the timeline, reaching further and further for the heavens.

Once the individual tree has passed the Torch, once it has reproduced, the tree’s ‘mission’ is complete—it has fulfilled its biological design, its purpose—and then the tree dies. However, that death is not the end of its chain, and therefore shouldn’t be interpreted as ‘tragic.’ It’s simply part of the cycle, a mechanism built into the Torch.

The animal kingdom lends us even more striking examples of this concept, often because the lack of individualism is so abundantly clear.

With honey bees, for instance, each bee is one member of a hive, and each hive is one iteration in a lineage of hives. The individuals do not live ‘every bee for themselves,’ they display a very complex cooperative behavior which benefits the hive. This does not mean the individual bee’s existence is unimportant or meaningless, it simply means the bee is part of a whole.

And, again, that whole is not just multi-individual, it’s multi-generational. It’s more than just a single, physical hive, it’s an ongoing string of hives that link back to the first life form and extends onward into the future for many hives to come.

To illustrate, honey bees will sting attackers, often killing themselves in the process. The stinger gets ripped out when they do this, which ruptures their abdomen, and they die. If bees were truly individuals, why would they kill themselves? Wouldn’t they instead opt to keep living at all costs? Wouldn’t they quit being a worker, leave the hive, and go snort pollen in their own private flower bed?

No, because if the bee could be said to have a ‘self,’ it would be more accurate to say that self was the hive. In stinging an intruder, the bee protects the hive, therefore protecting its ‘self,’ even though it dies in the process. It’s deeply counter-intuitive to our modern sensibilities, right? That something could protect itself and die at the same time.

However, it would be even more accurate to say the self is not the hive, but the bee’s Torch. The bee doesn’t only sacrifice itself to contribute to the success of its hive, but all future hives, to pass on what was handed to it by all previous hives, to protect—you might say—the great posterity of ‘beedom.’

Another example is that certain species of ground squirrels call out when a predator is near, to sound the alarm for their kin. In doing so, the individual gives away its location to the predator—making it far more likely to be found and killed—but protects its relatives, protects its descendants, protects its Torch.

In certain species of spider, the female eats the male after they mate! Again, how could one possibly help ‘itself’ by dying in the process? But it does, because the real entity is the lineage of spiders. By mating, the spider passes the Torch and, therefore, completes its mission—even though it dies in the process.

So life is an entity that defies the eroding sands of time, a pattern that perpetuates into the future by passing its genetic code along a chain of material manifestations. It’s a precious package of energy that builds itself into a temporary protective avatar that can carry that package and pass it along to another avatar before the current one disintegrates.

That avatar might be a grove of aspen, it might be a fungus colony, it might be a pack of wolves. All of them are defined by the bundle of energy they carry, which all of their traits and behaviors are designed to protect and pass along to the next generation, who will then pass it to the next generation, and so on, forever.

And so we arrive at the crux of our argument: what about humans? Do they follow this pattern? Are they burdened by the responsibility of the Torch? Do they behave—not as individuals—but as part of something greater than themselves?

Of course they do. Though many of us seem to resent it. Humans are a form of life. All of their traits, structures, and behaviors are aimed at something like ‘survival,’ but not specifically the survival of the individual, rather the survival of their children, survival of the tribe, survival of the Torch.

It makes sense that men will risk their lives hunting to provide for their family. It makes sense that women will risk their lives in childbirth. It makes sense that they will both break their backs laboring all day to take care of people other than themselves. Humans readily sacrifice their individual bodies and lifetimes for the lineage which transcends them, which extends beyond their material existence.

Their bodies, their minds, their morality, the very objects they perceive all revolve around making sure this Torch gets handed off to the next generation. They might not be conscious of it, they might not say it out loud, but that’s what they’re doing.

For instance, there is no escaping the fact that we obsess over sex, that we crave romance with a deep passion, because it is the act of reproduction, because it is the act of passing the genetic Torch, which lies at the heart of our existence. If participating in the propagation of a lineage, if existing as a manifestation of sacred stream of energy that transcends us, were not a thing—if we were truly individuals—sex wouldn’t exist. There would be no need for it. We would just be egos floating around, masturbating in space, doing things simply because they feel good, and trying to live forever at all costs.

But we are not that. We are that which passes the Torch. We are life.

However, there’s an important wrinkle here we cannot forget. Humans are life, but they’re different than other forms of life, and this is key: humans have culture. They’re conscious; they pass knowledge and ideas to one another through language; they convert their environment into tools; there’s entire systems of ethics that they maintain, share, and pass on to their children.

So, for humans, the Torch is not just genetic, it’s cultural. Their behavior, the way their bodies and minds are structured revolves around reproduction, yes, but also around a collective enculturation between kin and their offspring—developing language, technology, craftsmanship, art, rituals that will all aid their descendants in their mission of carrying the Torch, and then passing that Torch onto their offspring, and so on.

Beyond that, humans aren’t solely securing the reproductive success of their children, but their tribe—their siblings and cousins and their cousin’s children. Humans are tribal, and the tribe is an entity that is multi-individual, multi-generational, that transcends any one physical manifestation. Everyone in the tribe will die someday and, yet, the tribe keeps going. Every brick in the cathedral will crumble and need to be replaced, and yet the cathedral keeps standing.

And because humans are tribal and cultural, this means that humans have that great responsibility of carrying the Torch, whether or not they have children: they have a responsibility to cultivate and pass on good culture. And they can find immense meaning in this, they can discover powerful ways to contribute to the Torch outside of the realm of parenthood.

Think about Gandhi’s cultural contribution to the Torch. Or Plato. Or Jonas Salk. If they had been childless, would it really have mattered? No one can doubt the ripples they cast out into the world, well beyond their lifetimes.

So this distinctly human Torch is a great interweaving of biology and culture into a multi-individual, multi-generational package that we all contribute to with every breath, action, and word. This package is alive, blowing in the harsh winds of nature which is always trying to snuff it out. It can grow brighter and brighter as we innovate, develop, and feed it; it can easily become dim and weaken if we become negligent or narcissistic. If it weakens too much, it can extinguish; and if the Torch extinguishes, it’s gone.

We are all leaves on a tree—the Tree of Life. Come winter, we’ll turn brown and blow away with the wind. But we’ll take solace in knowing we got to feel the sun’s rays, that green leaves will sprout anew and take our place, that the Tree will keep reaching its branches further and further towards the stars for many seasons to come, that we participated willingly in the mystery of life.

Thank you for this - the symbol of the torch is an interesting addition to this topic. It gives a wider perspective to the old idea of 'meaning', 'purpose' etc.

I have been watching a lecture series on YT by Robert Sapolsky on Human Behavioural Biology and I enjoyed how this also very much related to that genetic behavioural thread and how you connected culture into that.