The science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick (1968) begins with a critical moment in human history, in which our primate ancestors broke away from the rest of the animal kingdom onto an evolutionary track that would eventually produce consciousness, language, and technology.

The movie calls this the ‘Dawn of Man’: the moment that humans are born.

In the film, a tribe of primates wanders an African grassland scrounging for food. They toil through the dirt, competing with local fauna for measly shrubs and roots, and are regularly killed by predatory cats who rule the land. The primates are not at the top of the food chain. They are barely surviving.

At their watering hole, they are chased off by a rival, more dominant tribe of apes and forced to retreat to their dwelling on the side of a cliff.

When they awake the next morning, a large black monolith (presumably put there by aliens) is standing upright before them. Terrified at first but overcome with curiosity, they each come to place a hand upon the alien artifact, which brings about a change in their psychology. It flips a switch. It plants a seed. It incepts an idea that will forever change their evolutionary trajectory, and the world.

One of the changed primates goes on with his normal routine, roaming the grasslands and scrounging for food. As he scavenges amongst a pile of bones, he pauses, entranced by something he’s never seen before:

A thing. An object. Something external to himself that he can use.

The ape picks up a tapir’s leg bone. However, he doesn’t see a ‘bone,’ he sees a ‘tool,’ and after swinging it about a few times, he comes to see a ‘weapon.’

This is the great moment of transformation.

It is the birth of techne: the ability to create—and therefore manipulate—objects.

What do I mean by this?

The very first sequence of 2001, before this ‘Dawn of Man’ first act, is several minutes of black screen and eerie choral music, conveying the nothingness of preconsciousness.

No-thing-ness.

Prior to their contact with the monolith, the primates see no-thing; they are not yet conscious; they are not yet the thing that makes humans human. After touching the alien artifact, they begin to see things; they begin to differentiate things out of phenomenological fog of being; they go from no-thing-ness to thing-ness.

So where the apes once followed their instinctual, unconscious programming day-after-day, never registering any thing around them, they’ve now interrupted that programming to register an object: something external to their unified oneness with nature; something external to their unified oneness with the unconscious; something that can be used for any number of purposes. In this case, a weapon.

Soon, the whole tribe of primates awaken, discovering their capacity for techne, and return to the contested watering hole. This time they come armed with clubs and beat the leader of the rival tribe to death, driving them out of their territory for good.

The first act then concludes with one of the victorious awakened apes hurling their club into the sky. The shot abruptly changes to that of a man-made satellite orbiting the Earth, millions of years later, and so begins the second act of the film.

The implications are that what started with a club made of bone, eventually leads to interplanetary space travel, and that the thing that accomplishes this—that sets humans apart from the rest of the animal kingdom—is techne.

The power of techne quickly comes to dominate the ecosystem, with these awakened apes rapidly outcompeting everything around them, adapting to every environment, spreading throughout the entire planet, and eventually giving birth to technological marvels such as computers and space ships.

Meanwhile, to this day, their closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, still reside in small kin groups in the same forests they’ve been living in for millions of years. We went to the moon while they stayed in the bush, all because of this powerful and mysterious psychological innovation of techne: the ability to create, and therefore manipulate, objects.

Techne means ‘art’ or ‘craft’ in Greek. The machines produced by techne—whether concrete or mental—we usually call ‘technology.’

But what do I mean by the word ‘object’? How does that lead to technology? And how does it relate to things like language and consciousness?

First, we’ll start with what objects are not: they are not made up of matter; they are not material in that sense. Rather, they are psychological projections we throw onto the material world in order to manipulate it. That is because we do not perceive the material world itself, we can only use our senses—like sight and touch—to take in information and try our best to predict ‘what is there’ and how we should engage with what is there.

So reality, as we think of it, is a landscape of projections, rather than a landscape of physical matter. It is not something we simply open our eyes and observe; it is something we actively generate.

To illustrate, let’s say you’re out hiking and, off in the distance, you see what you think is an animal. As you cautiously get closer, you realize that what you saw is in fact just a tree stump.

How can that be?

The material thing that was ‘actually there’ did not transform from a deer into a mass of wood. Rather, you predicted two different things—an ‘animal’ and a ‘tree stump’—based on your proximity to the materials and, consequently, the amount of sensory information you were able to work with.

We know this. It happens to us all the time: we think we see something or hear something or feel something, only to realize later that it was something else. ‘Reality’ is not simply observed, it is projected.

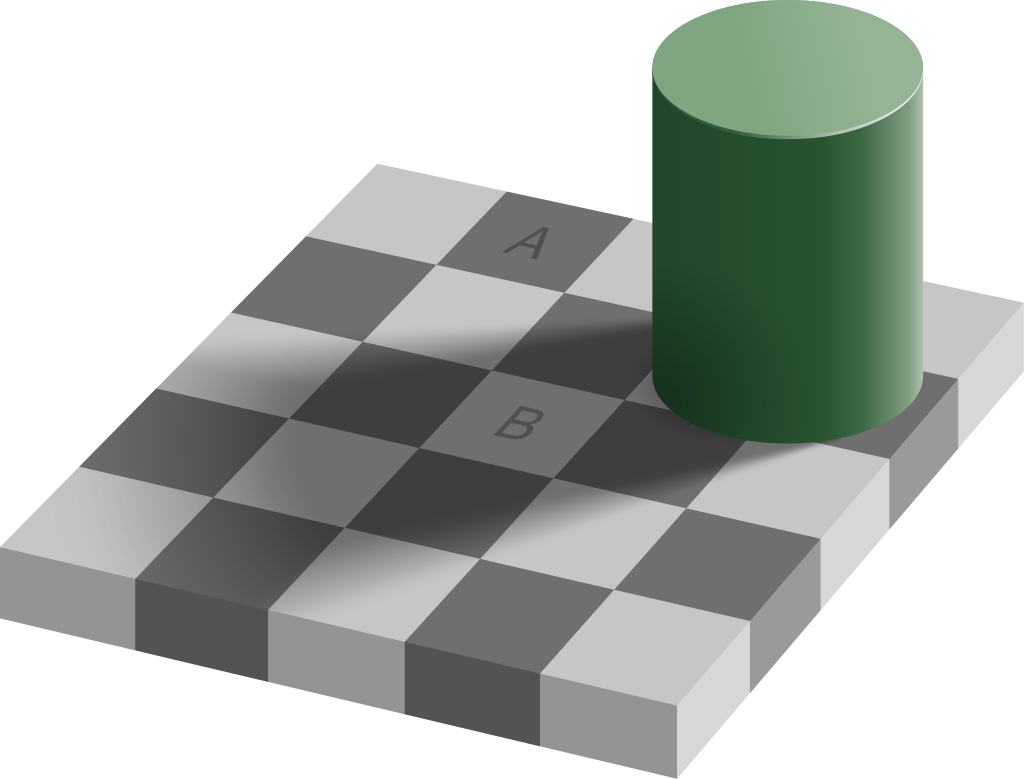

An easy way to play with this is the optical illusion, in which the brain is ‘tricked’ into projecting a pattern that isn’t there:

Look at the image below. The squares marked ‘A’ and ‘B’ look like they’re different colors, different shades of gray. Square A’ is clearly darker than square ‘B’, right?

However, the next image shows that they are, in fact, the same color:

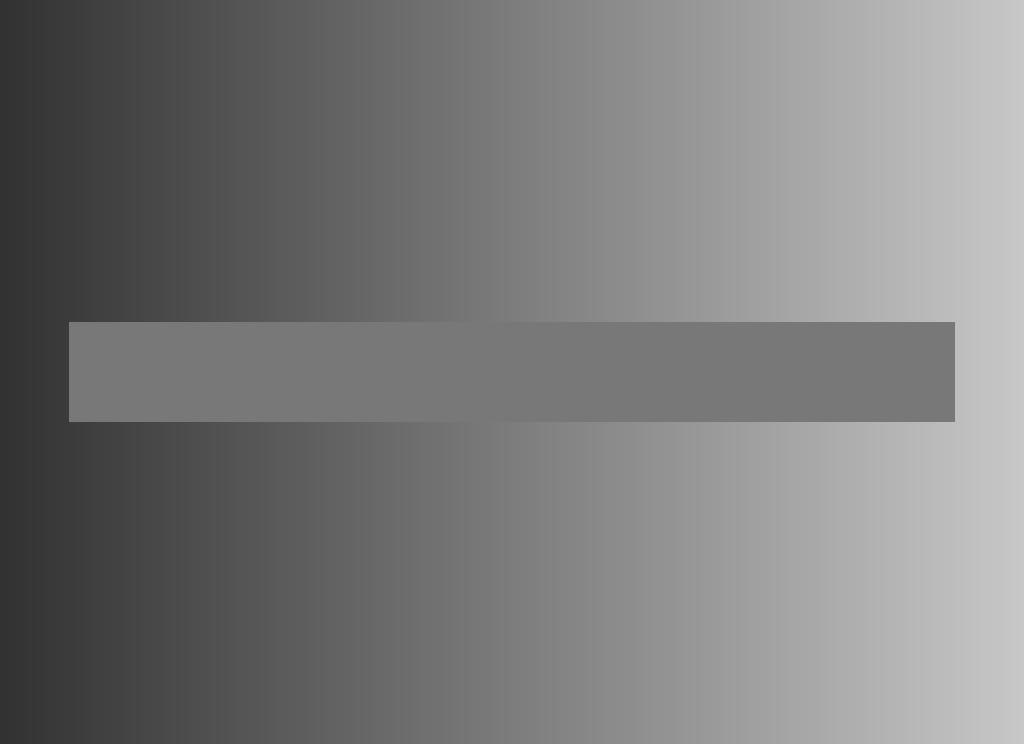

For this next one below, the background is a gradient from dark to light. The gray bar in the middle looks like it also has a gradient… but it doesn’t—it’s actually one solid color. Try to observe yourself succumbing to the illusion in real time.

With this one, the lines are parallel to each other, perfectly horizontal, but they appear sloped due to the positioning of the black squares. Your projections are showing!

Here, try moving your head towards and away from the screen, back and forth, to perceive the wheels as moving. The wheels, of course, are not actually moving, the pattern is messing with your projective faculties.

These optical illusions are simple, but effective in demonstrating the fallibility of our projections, in demonstrating the fluidity and fuzziness of reality. We don’t just observe what is there, we actively predict what is there—and we often predict wrong.

So reality, as we think of it, is a landscape of projections.

Returning to objects, consider that the world upon which we throw these projections is overflowing with information. It’s noisy. So when we we try to predict what’s there, the incoming sensory information all blurs together, which makes it difficult to work with. How can we follow a conversation if dozens of people are all talking at the same time? How can we make out an image if it’s been overlayed with hundreds of others?

In order to navigate a noisy reality, we reduce the incoming unconscious information—we compress it—into conscious compartments that we perceive as ‘objects’. We reach into the fog of being, the undifferentiated phenomenological backdrop of no-thing-ness and pull out a thing. This compartmentalized world is now easier to navigate, easier to manipulate, easier to conform to our needs.

We can now engage with our surroundings in a dynamic, adaptable manner, which is what humans do. Put a human into any habitat, and he will deconstruct and reconstruct it to fit his needs. That’s what allows him to live in almost any environment on the planet.

Though most of our psychology is ‘built-in’, objects are not. They must be actively created by each individual. Therefore, each of us carries around with us a unique collection of objects that we’ve personally created over time, instinctually, from the moment we were born.

To illustrate, if you’ve ever found yourself in a situation where you lack expertise, another way of saying this is: you haven’t yet created the objects relevant to this particular context, domain, or medium.

Let’s say a carpenter is working on your house and asks you to hand him a ‘jigsaw.’ You don’t know what that is—you have no ‘jigsaw’ object, you’ve never needed to create one in your mind because you’re not a carpenter. He then asks you to hand him a ‘speed square.’ What the hell is that? You’ve never created that object either. How about a ‘monkey wrench’? Well now you’re just making things up!

Realizing your lack of expertise—your lack of objects relevant to carpentry—he takes you over to his collection of tools and points to the first one. As you follow his finger to this novel thing, and hold it in the spotlight of your mind, he says the word, ‘jigsaw.’ As he does this, you create a new object in your mind, called ‘jigsaw.’

Now you can identify a jigsaw next time you see one; you can learn how to use one; you can go to Home Depot and buy one; you could even theoretically build one yourself. That is all to say: your creation of the ‘jigsaw’ object allows you to interact with and manipulate your reality in a way you couldn’t before, just like the ape in 2001 did with the bone.

Also, objects are hierarchical, meaning they have other potential objects nested within them.

For example, the ‘guitar’ object has nested within it a ‘neck’ object. The ‘neck’ object has nested within it a ‘frets’ object. The ‘frets’ object has nested within it a ‘5th fret’ object. And so on. Objects within object within objects.

By breaking down objects hierarchically, we can refine them, map them out, and integrate them into our physiology. We usually call that ‘learning.’

To illustrate, imagine your child—a toddler—has never actually seen a guitar before. So first, you teach them the meta object of ‘guitar.’ Maybe you then break the ‘guitar’ object down into ‘strings’ and ‘frets.’ As they get older, you break the ‘guitar’ object down even further for them: ‘E string,’ ‘B string’, ‘G string’... ‘1st fret’, ‘2nd fret’, ‘3rd fret,’ and so on.

As they internalize these objects—nested within the meta ‘guitar’ object—they build upon them to create more complex objects, ‘D chord’, ‘A chord’, ‘G chord,’ which themselves are made up of the ‘first string’ and ‘second fret’ objects plus the ‘second string’ and ‘third fret’ objects... and so on.

As they repeat this process, they ingrain the objects into their physiology: they place fingers on the appropriate string objects, and the appropriate fret objects, and then strum. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. Objectifying, and objectifying, and objectifying.

By repeatedly breaking the guitar object down into mesa objects (‘2nd fret’), then synthesizing them back up into refined meta objects (‘guitar’), they learn how the object is structured and how it functions, and expand and refine its utility by developing an increasingly complex relationship with it.

The more they objectify and engage with the ‘guitar’ object, the more conditioned their interactions with it become. The object gets etched into their physiology with each projection, with each engagement, each repetition, and their relationship with the object can become so developed and complex that it eventually becomes a skill.

Eventually the complex hierarchy of objects is so ingrained, they no longer have to consciously objectify at all. It just becomes second nature and they can play without even thinking about it—much like an adult speaks English or drives a car.

Through repeated, progressive, hierarchical mapping of the guitar object, your child constructs the personal machinery—the technology—of guitar-playing. That is the power of techne, a power mastered by humans, that defines what they are.

Things get a little stranger, and less intuitive, when we come to realize that objects are not restricted to external, ‘physical’ things in our environment—like ‘chair,’ ‘cup,’ or ‘guitar’. That they can be things of the ‘inner world’, purely abstract, mental, or even fictional.

For instance, if we watch a movie like Star Wars for the first time, we create the new objects ‘Darth Vader,’ ‘The Empire,’ ‘Leia,’ ‘The Rebellion,’ and ‘Luke.’ We do this in order to follow the story and make sense of what’s happening. If we didn’t, there would be no narrative—no movie—it would just be aesthetic noise. Luke using the force to destroy the Death Star wouldn’t induce any kind of emotional climax or narrative catharsis if you couldn’t keep track of who the ‘Luke’ object was, or what the ‘Luke’ object had to overcome.

Someone showing up late to the movie—having no opportunity to create the proper narrative objects from the beginning—would demonstrate that lack by saying things like, “Who the hell is talking to Luke in the X-Wing? Some kind of ghost? What’s ‘the Force’? Why did he blow up that space station?” Another audience member might have to catch this person up, specifically by giving them the narrative objects they missed. “Well the ghost talking to Luke is ‘Obi-wan’ (new object) and the space station is called the Death Star (new object)…” and so on.

The key point is that these objects aren’t ‘physical’, I can’t reach out and touch them. Sure, I can focus on the objects ‘Han Solo’, or ‘Tatooine’, or ‘The Force’, or even the history and lore of the Jedi, but I can’t sit inside the ‘Millennium Falcon’ object or hold the ‘lightsaber’ object in my hand. And that makes the nature of their existence confusing.

See, even though Luke is an immaterial fictional character, I’ve still projected him onto my reality. ‘Luke’, the object, has a white shirt, blonde hair, and a blue lightsaber. He’s a teenager who grew up with his aunt and uncle. He’s brave, heroic, and a good pilot.

I can engage with ‘Luke’, the object, by drawing a picture of him; I can do an impression of him; I can quote him; I can dress up as him for Halloween... and yet he’s not a material thing. Though there are many representations of him scattered throughout popular media, he does not exist anywhere in any physical sense. He is an object of fantasy.

That is to say, techne is not restricted to projecting objects into the physical world around us, but is the ability to create actionable units of reality that occupy the realm of ideas, concepts, and narrative. In fact, we will come to realize that most of our objects are like this: they lack a specific, physical manifestation, and instead occupy a place of abstraction and metaphor.

As we explore the concept of techne more deeply, we’ll come to notice that it’s strongly associated—you might even say synonymous—with language.

That’s because techne is a distinctly social innovation. It evolved because our primate ancestors needed to work together as a tribe in order to survive.

See, techne not only helps us compress and manipulate the world around us on a personal level, but—more importantly—helps us do it with others. Instead of each individual having to objectify the world in a vacuum, from scratch, we can objectify the world as a team, with other minds working in concert, creatively innovating with these objects, developing them, and exchanging them.

That is why techne and language evolved together, simultaneously, in a kind of evolutionary feedback loop; the creation of objects yielding language, and the innovations of language yielding more objects.

The best way to understand this is to simply observe that words are objects, by their very nature. Every single one. If there’s a word for something, it’s an object. If an object is exchanged between minds, it almost always has a word slapped onto it.

The realness, or concreteness, or utility of that word can vary wildly; but if there’s a word for it, it’s an object.

We use words to organize our reality, to distinguish objects from one another, to differentiate objects away from what they are not, but especially to exchange these objects with other minds.

Let’s say I’m an ancient ape, and there’s an object I’ve created, one I’ve projected onto a tapir bone. Unconsciously, implicitly, the object is something like ‘thing-that-smashes’. But to breathe more life into the object—to make it more useful, powerful, wieldable, and shareable with others—I’ll make the object explicit, I’ll bring it into consciousness, by giving it a name: ‘club’.

Now that I’ve named it, I can refer to the object out-loud, with others. “What is that? It’s a club.” I can better organize my objects when they’re named, by doing things like referring to the object on my to-do list: “Find more clubs”; or journal about the object: “Today, I accidentally broke my club. Perhaps I should be careful not to accidentally swing it into the ground.”

Giving an object a name, making it explicit, makes it more real. But most importantly, I can now engage with this object in cooperation with other humans, I can share my reality with another mind: “We should find more clubs and teach others how to use them.“ “How did you repair your club after it broke?” “Can I borrow your club for a moment?” Through these words we can share the ‘club’ object with each other, refine it, discover its properties and through that process make more and more sense of the world as a place of objects—an objective reality.

Importantly, once techne gives you language, it also gives you culture.

Objects that can be passed from mind to mind, through language and demonstration, yields a collection of objects over time that the tribe maintains, augments, and refines. Just as they pass this collection back and forth to their peers, they pass it down to their children. In doing this, you get a set of objects that is now intergenerational; a living, breathing landscape of ideas, stories, skills, knowledge, ethics, and rituals that gets passed on from generation to generation. That’s what culture is.

If objects are mentally generated, rather than simply observed, then what decides the nature of these objects? What decides their features and qualities, the way they reveal themselves to us? What decides their aesthetic properties—like color and smell—or moral qualities—like ‘appetizing’ and ‘beautiful’?

Just like we confuse ourselves into thinking objects are physical, material things, we confuse ourselves into thinking that objects are neutral or hollow containers without a moral component—but this is wrong. Reality is moral. Objects have a kind of should or should-not built into them. And that moral component of objects comes from their perceived utility, purpose, or relationship to our existential goals.

In other words, objects—by their very nature—are tools. That is why the ability to create objects is called techne and the machinery we produce from objectification is called ‘technology.’

What do I mean?

Every object has a kind of usefulness to us. Maybe its usefulness is positive, meaning it helps us get what we want; maybe its usefulness is negative, meaning it prevents us from getting what we want. Whatever the context, the utility of a thing is what makes it what it is. It is, specifically, what makes a thing appear to us the way that it does, what determines the nature of our projections.

The monkey’s ‘club’ object, for instance, is not just a neutral material thing—it’s a tool, it’s a package of affordances. What makes it a ‘club’ is that the monkey understands it can smash things, that it’s not too heavy to wield, that it’s not too fragile to break, that it can lead to food. It serves a purpose for the ape—that’s the only reason it even notices the thing in the first place, the only reason it differentiates the object out of the fog of unconsciousness. If it was ‘neutral’—if it had no utility—it would never have been noticed, it would never be differentiated, it would never become an object in the first place. As far as the ape is concerned, it wouldn’t exist.

A cup is not a neutral thing, it’s a ‘liquid-holder’. A hat is a ‘shade-provider’. A car is ‘thing-that-transports-me-to-where-I-need-to-go’. These are all defined by their affordances.

Because of this, the nature of an object—the way it reveals itself to me—can fluctuate based on the problem-at-hand. Change the context, change the utility, change the object. A fallen piece of wood is not simply a ‘branch’—this neutral, empty thing—it is whatever tool I project onto it. Maybe it’s a ‘club’; maybe it’s a ‘spear’; maybe it’s a ‘walking stick’; maybe it’s a ‘flag pole’; maybe it’s a ‘fence post’; maybe it’s ‘firewood’. The materials stay the same throughout each example, but the object projected depends on its perceived utility to me.

Contrastingly, the same object might be projected onto many different materials: a stool, a bucket, a tree stump, and a boulder can all have the object ‘chair’ projected onto them. They’re all very different materials, but when the problem-at-hand is ‘finding-a-place-to-sit’, they all become ‘thing-to-sit-on.’

By projecting objects onto the environment, we transform it into actionable units that can be engaged with, repurposed, and adapted to our needs. Without objectifying the environment, we are like animals: we cannot adapt our surroundings into tools. We still have all of our preconscious circuitry and instincts to guide us—like a dog or bird—but we cannot take a stick and project 40 different uses on it; the stick simply recedes into the noisy backdrop of unconsciousness and remains undifferentiated scenery.

But if we formulate objects according to their utility, what is that utility based upon? What governs it? If objects take a certain form that reflects their use to us, what exactly are they useful for?

The nature of all objects—not just the way we see things but the very things we see—is dictated by its relationship to the Torch. Objects are tools, and the tools we see are what they are based on how they help us pass the Torch, how they help us protect, promote, and propel our package of genetic and cultural information into the open future.

Essentially, everything we see, everything we perceive in the world and the way we perceive it, appears to us as it does for the purpose of optimizing our collective ability to make babies, teach them things, and ensure they survive.

I project ‘liquid-holder’ onto a cup because holding liquid is useful to me, because I need to drink fluids, because I need fluids to survive, and I need to survive so I can pass the Torch. I project ‘thing-that-cuts’ onto a knife because cutting food helps me eat, because I need to eat to survive, and I need to survive so I can pass the Torch. I project ‘music-channeler’ onto my guitar because creating music is useful to me, because its a social cultural glue and narrative device that keeps the tribe in cultural resonance across generations, and keeping the tribe in resonance helps the tribe survive, and the tribe needs to survive to keep the Torch alive.

The very colors, and textures, and smells we perceive are tools. They are projected utilities. When we talk about ‘aesthetics’ we are recognizing that the qualities and properties of things we perceive have value baked into them. If something has a positive relationship to the Torch, we might project beauty or attractiveness onto it; if something has a negative relationship to the Torch, we might project ugliness or disgust onto it.

A woman who will help me carry the Torch, make it grow bigger and brighter, and ensure it gets passed onto a new generation is going to be very beautiful to me. A mountain of rotting trash that is full of bacteria and disease, which could spread to me and my tribe and snuff out the Torch, is going to be very ugly and repulsive to me.

That is to say, what we call ‘reality’ is a landscape of utilities, compressed into discrete tools, whose structure, appearance, and vibe is reflective of its usefulness towards passing the Torch. The Torch not only structures the way we see things, but the very things we see; the Torch not only structures what we perceive to be ‘real’, but reality itself.

So, techne is what makes humans what they are, what made them break away from the rest of the animal kingdom, what made them split from their chimpanzee brethren seven million years ago. It changed everything: humans became tool-users, language-speakers, culture-wielders, and took over the planet.

However, their capacity for techne introduced novel and complex problems, because recognizing the world as a place of objects eventually meant recognizing the object of ‘me’, recognizing the object of ‘time’, and recognizing the object of ‘death.’

It also led to the development of technologies so powerful they exploded population densities, trashed the environment, radically transformed lifestyles, and brought about repressive social structures. And there is no going back.

The moment humans became technological, they began the long march out of the spiritual oneness of the preconscious Garden and into spiritual splintering of the Shadowlands.